How do we fix the Hauraki Gulf?

The once abundant Hauraki Gulf is on the brink of collapse, and while science is clear on how to repair it, many are putting rights before responsibilities. Here’s what needs to happen.

I’m going to start at home. Every summer, my family seconded ourselves to a fibrolite bach in a tiny bay at the eastern end of Waiheke—a large, verdant island at the centre of Auckland’s Hauraki Gulf. We swam, built rafts, played in the bush fringing the beach, and at low tide explored the rock pools, marvelling at the creeping and crawling things within them—glass shrimp that would nibble at your fingertips if you remained still, and cod that hid beneath the rocks and lay slimy and cool in your palm.

There were sprats and piper in the bay. Eagle rays and short-tailed rays took turns cruising in the sandy shallows. The biggest ones—perhaps two metres across—would eat out of our hands, if we were brave enough. Sometimes the calm of the bay would be disturbed by a salvo of fish leaping from the water, pursued by a kingfish. More rarely the rays would flap in the shallows, driven to the edge by a pod of orca that emerged dark and fast from the adjacent bay, their sharp breaths like gunshots.

Some days, schools of kahawai would sweep into the bay, and the surface of the water would boil white as they chased the bait fish. We could row in a dinghy with nothing more than a white rag on a hook and be sure of a strike. At any moment there was a boil-up somewhere in the Waiheke Channel, usually a few, attended by a cloud of white-fronted terns whirling above, and gannets, searing through the blue sky and headlong into the water like Exocet missiles.

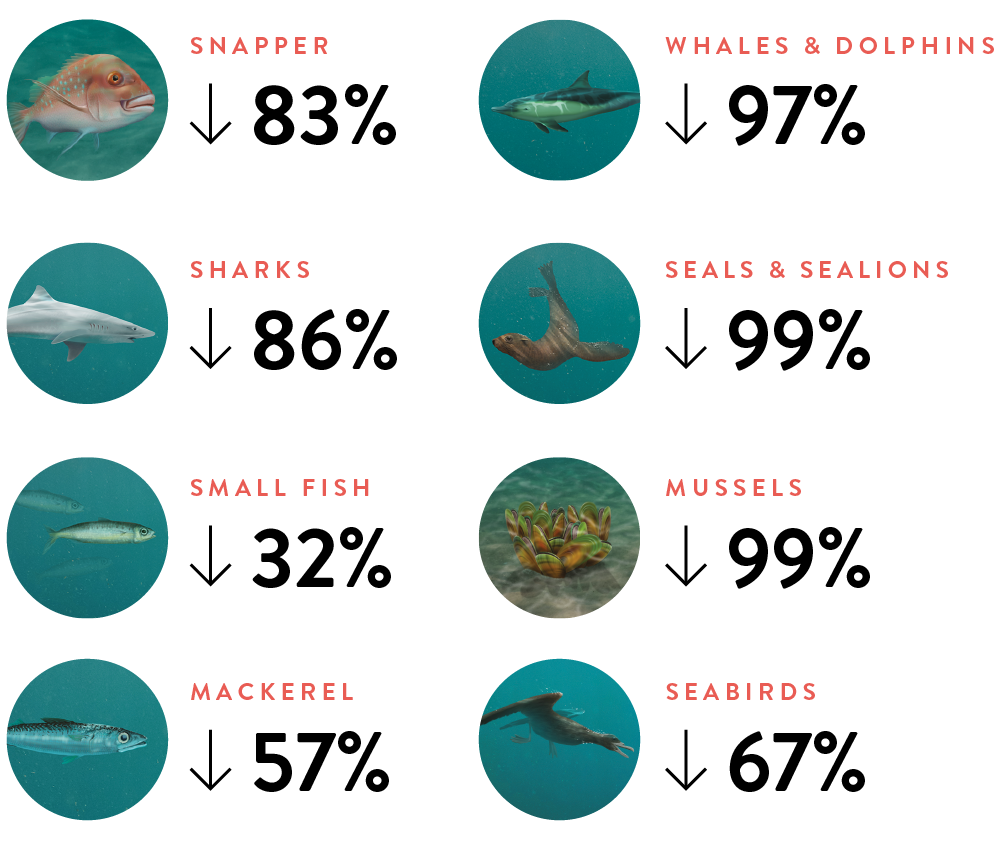

DATA: Pinkerton MH, MacDiarmid A, Beaumont J, et al. Changes to the food-web of the Hauraki Gulf during the period of human occupation: a mass-balance model approach. Wellington: Ministry for Primary Industries; 2015. And MacDiarmid AB, McKenzie A, Abraham ER. Top-down effects on rocky reef ecosystems in north-eastern New Zealand: a historic and qualitative modelling approach. Wellington: Ministry for Primary Industries; 2016.

We weren’t big fishers, but there was plenty of fish to eat—we would drop a line or set a net since there were no shops for miles around. Often a kahawai or two, maybe a snapper, occasionally gurnard. We’d sit on an upturned bucket in the shallows and fillet our catch as Dad had shown us, tossing the guts and skins to the black-backed gulls that nested on the point year after year.

My grandfather would knock a clump of fat oysters off the boat ramp into a tin bucket, then sit on a nailbox (the same one he dragged me up and down the beach on as a baby), shucking them with a butter knife in the shade of the boat shed, eating them on the spot. I preferred the mussels, which hung like bunches of grapes beneath the weed on the rocks at low tide.

Our take was small in the scheme of things, but taken nonetheless.

My dad and grandfather regaled us with stories of what it was like when they were young—the abundance of mussels before the dredging in the 1950s, the profusion of snapper and piper and kingfish. Their stories were as unbelievable to me then as mine are to my kids now.

Today, the ramp and rocks are covered in invasive Pacific oysters—all shell and no meat—and tangled in monofilament fishing line that has drifted in from the channel. Out on the point, a dune of sediment 40 millimetres thick is creeping over the reef, consuming the algae and oysters like a desert swallowing up a forest. The great boil-ups of kahawai have diminished to an odd occurrence. Sometimes, a month can go by without so much as a splash. The colony of white-fronted terns that perched in their hundreds on a rocky promontory two bays away has gone altogether. The water in the bay still sparkles in the summer, but life has been drained from it.

Writing these things isn’t easy. Confronting the loss stirs something sickening inside me. I’ve felt myself well up with tears, inconveniently, during meetings with important people. I’ve been prone to outbursts and emphatic language. I’ve offended people.

Part of my fury is that a great portion of the loss could have been prevented easily. We knew what was required to fix it, but some who felt they had a right refused to acknowledge that it came with a responsibility. Greed triumphed over stewardship. Despite the efforts of some to muddy the waters of the problem, there is no doubt about how to fix the gulf. It just hasn’t happened yet.

*

WHAT WE KNOW

You might be forgiven for thinking plastic straws or beach litter stole the soul of the Hauraki Gulf. But you could remove every nanoparticle of plastic from the gulf and it would die all the same. Its major problems are far more basic—they have to do with what we take out, and what we put in.

Only four of the most commonly caught fish in the gulf are at or near sustainable levels because—please brace yourself for a dose of the obvious—we ate them.

Or we sold them for others to eat. Crayfish are functionally extinct in the gulf because we tore them out of their rocky crevices and boiled them. There isn’t much in the sea because, generation after generation, we took it all out.

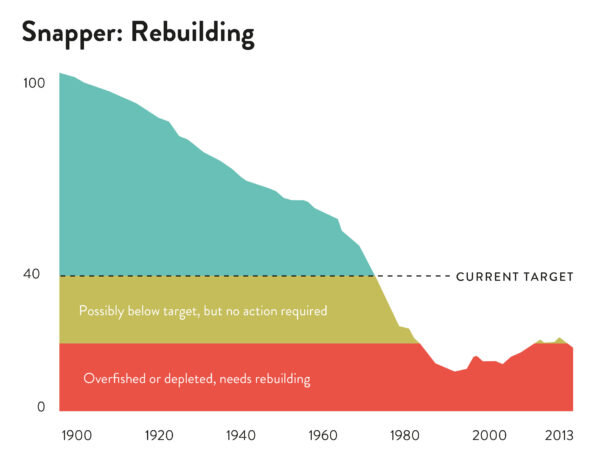

Many recreational fishers say their take is inconsequential compared with the commercial harvest, but this is a myth. Both take roughly equal numbers of snapper from the Hauraki Gulf, a stock that has plummeted to about 20 per cent of its natural abundance, with far fewer big fish.

Habitat destruction is still happening in the gulf on an industrial scale. A trawl line bisects the Hauraki Gulf from Kawau in the west to the Motukawao Group in the east. South of the line there are restrictions, but in the two-thirds of the marine park north of it, commercial fishers are allowed to dredge, bottom-trawl and practise Danish seining, which destroys the fragile structures on the seabed and reduces the ability of the marine ecosystem to sustain itself—and us.

Sediment and nitrogen flood into the Firth of Thames on a daily basis from 5500 linear kilometres of waterways in the Hauraki catchment. Some 3600 kilometres run through intensively grazed farmland with little or no riparian planting, which would act as a filter. The result is a gulf choked with sediment and fouled with toxic algal blooms.

*

HOW WE FIX IT

This is simple: Reduce what we take out. Be careful with what we put in. Protect and restore habitats.

1. Stop destructive recreational fishing. Rods and spears give an angler the opportunity to choose what they land, but set nets and set lines are indiscriminate, killing sharks, rays and a host of non-target species that would otherwise contribute to the ecosystem. Likewise, scallop dredges destroy the seabed, and should be banned.

2. Stop destructive commercial fishing. Dredging, bottom trawling and Danish seining have no place in a marine park. They should be moved beyond its border either by legislation or as a voluntary concession from commercial fishers. A case could also be made for banning low-rent purse seining from the marine park. If we’re going to kill fish, let’s at least extract reasonable commercial value from them. Purse seining does not—fish are crushed in the process and useful only for low-value export.

3. Protect the marine environment. Scientists agree that protecting a portion of our marine environment from exploitation is critical for the health of unprotected areas. No-take marine reserves serve as fish pumps, amplifying fish stocks up to 40 kilometres away. New Zealand was the first country in the world to establish a marine reserve but has since lagged behind. While international scientists suggest 30 per cent of marine areas be protected by 2030, New Zealand has set aside just 0.37 per cent. In the Hauraki Gulf, where we need it most, just 0.3 per cent is protected. Current proposals will do little to change this figure.

4. Decrease the catch. Both recreational and commercial catch must decrease, a little, to move towards increasing abundance rather than declining abundance. It’s time for fishers to step forward, catch a little less, and preserve the future of the fisheries they love.

Comparison between the annual commercial (average 2016–17 to 2018–19) and estimated recreational (2017–18) catches of the top eight species caught recreationally in the Marine Park.

5. Seed shellfish beds. The Hauraki Gulf Forum has a goal of restoring 1000 square kilometres of shellfish beds in the gulf. There are some vexing scientific problems to solve in order to make this happen, but if successful, shellfish would provide crucial filtering, which helps prevent sedimentation. They’d also improve the health of the whole ecosystem, strengthening it against the effects of climate change.

6. Plant the edges of waterways. Both the government and councils are promoting large-scale infrastructure projects that will jump-start the economy after the COVID-19 lockdown. We have thousands of linear kilometres of waterways that need planting, and thousands of forestry workers—expert tree planters—waiting for Asia to begin importing logs again. Let’s put them to work.

7. Reduce carbon emissions. A healthy marine environment will be more resilient and will sequester more carbon than a compromised one. In the context of the Hauraki Gulf, emissions come primarily from our fleet of ferries, which consume 10 million litres of diesel every year. Electric ferries are waiting for approval. These would save that fuel and render $200 million over 20 years in savings.

*

The ecosystem at the doorstep of our largest city was once one of the most abundant on the planet. It was a Yellowstone National Park, a Great Barrier Reef, a marine park that should have been preserved in the same way we protect and preserve our national parks on land. Instead, we clear-felled it, like a kauri forest that was valuable only for the timber it contained.

Two decades ago, it may have been possible to tweak our behaviour and save the Hauraki Gulf from collapse. But now that it’s on the brink, we need to attend to all of these measures, all at once. It’s possible to fix the Hauraki Gulf now—and it won’t be possible later.

To save the gulf, we need to consider a future where rights are wedded to responsibilities. This notion may sound familiar, because it’s the principle behind kaitiakitanga—where harvesting from the gulf is connected to caring for the gulf, and guardianship is prized over ownership.

This story was first published in New Zealand Geographic, issue 163, May-Jun 2020.