Are fishos responsible for the decline?

This is probably a hard fact to face, but of all pressures in the Hauraki Gulf, fishing has had the single biggest impact. Both commercial and recreational fishers are responsible, but the balance has changed over the years.

The context of snapper, the rec fishing take has gradually increased (from 1334 tonnes in 2004 to 2068 tonnes in 2018—a 55% increase in 14 years), while commercial catch has decreased (from 1981 tonnes to 1096 tonnes—a 45% decrease in the same period). Today, rec catch is almost double commercial.

It’s different for crays, tarakihi and baitfish which have all been far more impacted by commercial than recreational fishing, but for snapper in particular, it’s as much on us as anyone… and recreational impact is getting bigger.

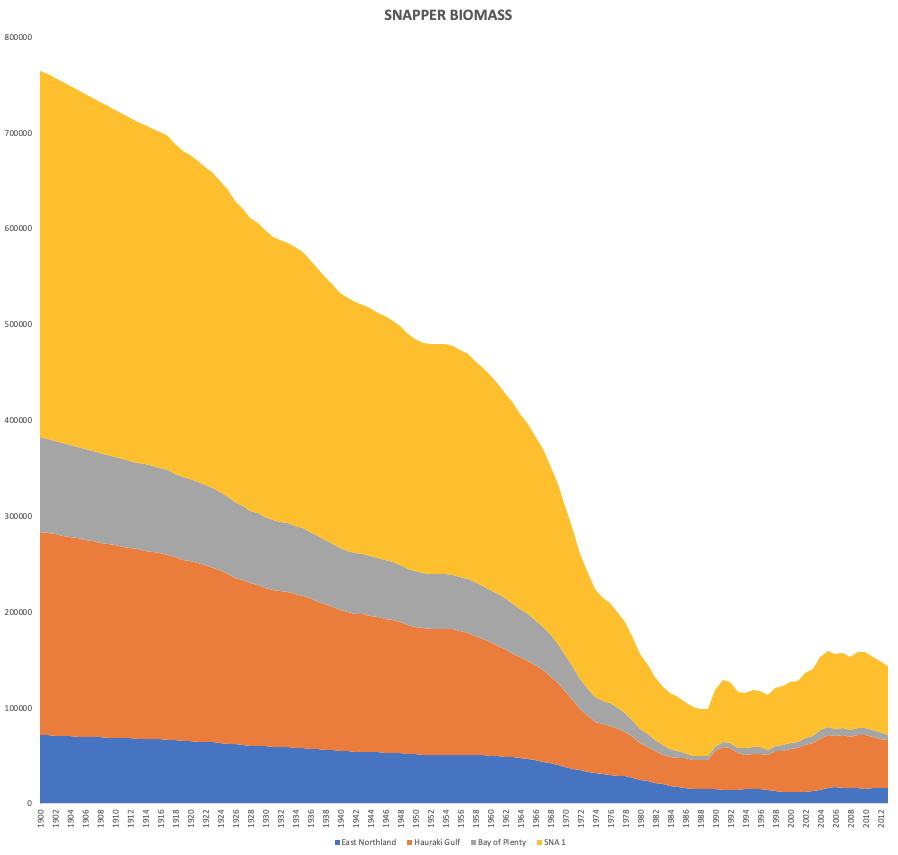

Recreational catch histories for the three areas of SNA 1 (Hauraki Gulf in red, East Northland in blue, and the Bay of Plenty in green). Open circles denote aerial-access survey estimates, closed circles recreational kilogram per trip indices scaled to the geometric mean of the aerial-access estimates, solid curved lines denote exponential fits to the scaled kilogram per trip indices which were used to predict harvests for those years for which creel survey data were not available, and dashed lines denote linear interpolations between 1990 and 1970 (when harvests were assumed to be at 70% of that predicted for 1990).

As a result, the total biomass of snapper in the fisheries management area SNA1, and in every region within it has crashed to less than 20% of original abundance. It has rebuilt slightly as a result of changes to bag limits in the late 1980s but there’s no doubt it’s still perilously low.

To put it in perspective, think of your greatest day fishing in the past 40 years, and multiply it by four times to get an understanding of how powerful this fishery was at the turn of the century. It must have been awesome.

NIWA/Bruce Hartill

The irony is that a century ago the Gulf could have sustained an annual catch of 3000 tonnes of snapper no worries, but not today.

If we take our foot off the gas, and allow the ecosystem to recover, it can and will become highly productive again. A study that looked at the closure of the Poor Knights demonstrated that snapper populations rebounded to 7.4 times the pre-closure abundance inside just four years.

We all want to return to a state of abundance, we just need to agree on how to get there.